The winter cluster

During September, workers evict the drones, and the number of honeybee workers reduces until 10-15,000 “winter” bees remain.

The winter bees start to be born in mid-August. Because they do little work, they live six months. To ensure they are healthy, varroa treatment must be applied immediately after harvest.

Winter bees have significant fat and protein stores (vitellogenin) but depend primarily on their honey stores. Some bees, like British Black bees, are thrifty and need fewer stores. Bees generate heat by contracting their elevator and depressor flight muscles simultaneously.

They start to cluster in a wooden hive (forming a ball of bees) at 14 °C. In natural bee tree cavities with walls averaging 14 cm wide, they cluster at minus 10 °C. In wooden hives, they cluster centrally.

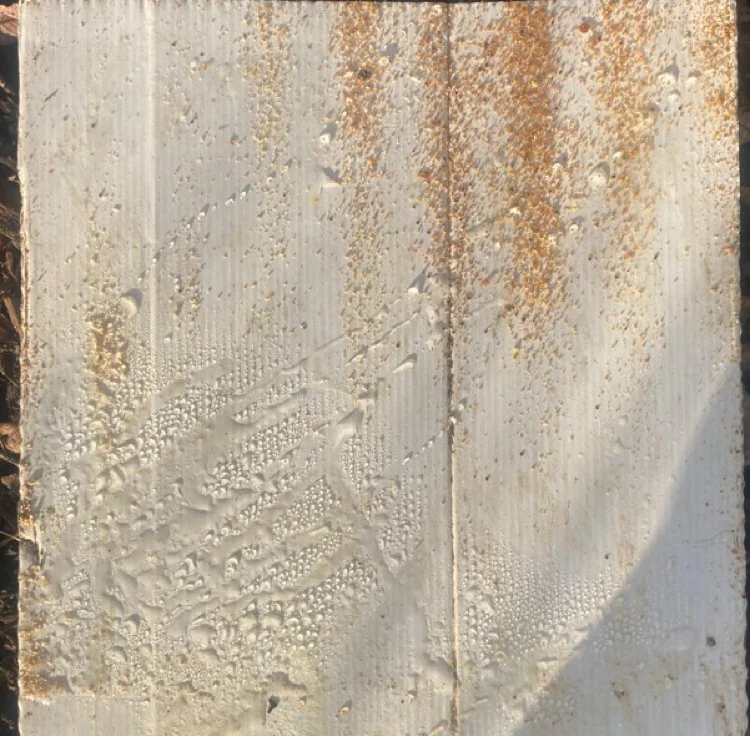

Bees in Beebox hives do not cluster when the exterior temperature is above 7 °C. probably less. One view is that in a temperate climate, bees rarely cluster in a poly hive. The pattern on the varroa board suggests they can move from one side to the other or to each quadrant in the horizontal plane. During the winter they usually cluster at the front of the hive in the bottom box; I find this counter-intuitive. Here are some Beebox varroa boards that indicate the positions of bee activities.

Varroa board (hive 8) December 2025

Varroa board (hive 8) January 2026

Varroa board (hive 1) December 2025

Varroa board (hive 1) January 2026

The queen is cared for in the centre of the cluster, where heat is generated. Her rate of lay gradually reduces until the colony has a brood break (a period without brood) in mid-winter, arising for a period sometime after around mid-November, about mid-December. At this time, the core temperature drops to 18 °C. Whereas, when brood is present, the core is kept at 34-35 °C. After the winter solstice, the Q is fed more, and her rate of lay gradually increases.

All colonies have a brood break, but not necessarily simultaneously.

In the cluster, the mantle bees push their heads into cells and are believed to form a significant insulating layer. Using a heat exchange mechanism in their petiole, they maintain the outer temperature of the cluster at 7–10 °C (depending on who you believe). Since bees become immobilised at seven degrees and die at 4 °C, the outer mantle bees are torpid. The belief that mantle bees rotate with bees further within is attractive but has not been scientifically demonstrated. However, when the cluster moves, the bees become markedly endothermic, so this must be an opportunity for the outer bees to jostle for a better position.

Honeybee cluster—not insulation but stressful heat sink

Derek Mitchel proposes that cold hive walls mean that the bees withdraw, seeking the warmth closer to the hive's centre. As the temperature drops, the cluster gets denser, and losses via conduction (from within) become several times greater than the losses from convection. The colder it gets, the greater the urge for mantle bees to get warm, so they push in, causing the cluster to become denser and less efficient to heat. Clustering results in transitioning from a state where the honeybees can suppress internal convection within the nest into a state of high internal convection and conduction. Their thermogenic aptitude falls off at 18 °C. To have to generate heat with further cooling is stressful.

Figure 10. Metabolic heat versus cluster diameter TA = −16.7 °C for various wall materials. Using National hive walls as shaded from the sky in still air. PIR = polyisocyanurate.

Derek Mitchell concludes:

“The conventional view does not match the recent advances in research and enables an avoidable increase in honeybee stress (i.e. refrigeration and use of hives not significantly different in performance from thin metal) when they face unavoidable increases in stress from pests, disease, and climate change …

… provoking behavioural survival responses for no benefit to the individual or groups of animals may be regarded as cruelty …..

…. changes in practice that reduce the frequency and duration of clustering should be urgently considered, researched and promoted ….”