Swarm Prevention

Encourage the queen to stay at home

Having learnt about collecting swarms, this is about preventing them in the first place.

Some methods involve changing the natural balance in the colony.

Introduction

When starting with a nuc in June, there is a low risk that they will swarm, but ensure the colony has enough space.

Throughout the spring and summer, a beekeeper spends more time monitoring and managing swarming than anything else. It is too late once a colony has started on the swarming trajectory. To stop a colony that is swarming, the colony is usually weakened; if they swarm early, say goodbye to a decent honey crop. Hence, the value of prevention methods to keep the colony together. One large colony produces more honey than two moderate ones.

I find the terms pre-emptive and proactive swarm control confusing. So, I’ll refer to swarm management techniques as:

Prevention, which is doing something to stop swarming from ever happening; it’s prophylactic, pre-emptive like an immunisation. And control, which is doing something to prevent the situation from getting worse that will lead to a cure, like isolating everyone who gets an infectious disease.

To completely prevent swarming is a bit optimistic; it depends on what and when you do something and a bit of good luck. Young queens in their first year swarm less frequently. But all bees attempt to swarm. It’s what they do.

The Initiation of Swarming

To understand swarming, it helps to appreciate the roles of pheromones (scent messages).

Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP) is critical in swarming. Weaker queens produce less Queen mandibular pheromone (QMP), which results in swarming. That’s simplistic, as QMP has five main chemical components whose proportions vary during a queen’s lifecycle.

In the normal life of a colony, messenger bees assimilate QMP by licking and antennating the queen’s (Q’s) mandibular gland. They pass it to other bees by sharing food, at which time they stroke their antennae. If the hive becomes congested, the bees and the queen move more slowly, and the workers at the periphery experience a reduction in QMP levels. The message reaches to the edge of the colony within minutes.

Tergal pheromone is synergistic to QMP in swarming initiation. It is released from the feet of bees as they walk. The chemical structure of the queen’s pheromone is different from the others and suppresses the formation of swarm cells.

Congestion: Based on some science, a simplistic belief is that swarming can be prevented by giving the bees plenty of room. But despite constantly feeding them comb, they still swarm. They swarm even when there isn’t an arc of stores, queen excluder, or nectar above the brood nest. Rusty Burlew explains why preventing congestion does not work.

QMP has broad effects, so for example, a fall in QMP is contiguous with a reduction in open brood (caused by the workers feeding the queen less food).

An American called Walt invented a method of swarm prevention called checker boarding, which he claims is 100% effective because it prevents the block to brood expansion. It requires prolific bees and young queens.

Swarming initiation takes place several weeks before the colony throws up queen cells. By the time the brood pattern changes, swarming is inevitable.

You should/could stop them swarming if you get them through their reproductive to their store gathering stage.

Factors that are associated with swarming

1. Time of year: occasionally late March, plenty in April, maximal in May and June, some in July, rarely in August and September.

2. Presence of drones in the swarming season, 9 -20% of bees in a wild colony are drones. A colony’s priority is spreading its genes, not making honey per se. Peak drone production occurs three weeks before swarming, but don’t count on it. The queen, on plastic frames, will only produce plenty of drones when you give her a frame without foundation.

3. Strong enough: This depends on how prolific your bees are. Mine will have ten frames of brood. Once, I had a swarm with six.

4. Plenty of queen cups, more than twelve.

5. Maturity / Constriction of the brood nest. Once there is a bit of back-filling, a little nectar in the upper or lower corners of the frames, the colony may swarm within three weeks.

6. Cold weather causes bees to hang around in the warm brood nest, and this causes congestion: 2.3 bees/square cm rather than 1.25/square cm will precipitate QC production, so check colonies as soon as the weather improves. Be quick! They may swarm by late morning.

7. Some stores indicate the maturity of the colony, but they are not an absolute necessity.

8. Recordings with specialist equipment and accelerometers inside the hive. Swarming can be predicted up to 30 days before the event with 90% certainty. Only researchers have used this method.

9. The queen’s age: 2nd year or more

10.“Splitting the brood” apparently, by putting a drawn or undrawn frame in the middle of the brood nest of a minor to moderate sized colony, it reduces the area for the queen to lay.

11. Genetics: some bee races, like Carniolans, are reputed to be more prone to swarming.

12. Anything that results in the bees sensing less QMP.

13. Plenty of young bees are required to comprise a swarm.

14. A honey flow in the spring or early summer keeps them busy. I don’t know whether this is real.

15. The queen has a lack of space to lay.

16. Using poly hives

Ways to reduce the risk of swarming

I’ve made a pretty list, but the most important factors are having a young queen and ensuring the colony has enough space to expand; despite this, they still swarm.

Wing clipping - see below

Let them draw wax Space

A good strain of bees

Young queen or two queens in one colony

Snelgrove (I)

Wing Clipping

This lies somewhere between prevention and control. Cutting off up to half of one of the queen’s longer wings makes her a weak flyer. Maybe she manages to fly a little way but soon drops to the ground, or she goes nowhere and crawls under the hive. The bees return home when they realise the queen is not with them.

Some beekers loathe maiming their bees; others swear by it. Should the clipped queen be lost, the colony has to wait for a virgin queen to emerge and then swarm with her, but meanwhile, you can do something to stop them.

To use this technique successfully, use a large landing board and do a severe clip of one wing (50%). This way, you should not lose the queen, and since she can crawl back into the hive. If she ends up under the hive with some bees, put a receptacle under her, dismantle the hive so that you can rattle the floor.

Clipping does not seem to affect the queen’s longevity or capacity. Insects are precious but single-use. Scientific investigation with accelerometers shows a different pattern after she has been clipped. Learn to clip wings without picking up the queen.

2. Space: Drawn Comb

A colony needs space because every activity requires drawn comb: space for brood, room for the queen to lay, a place for dumping and curing nectar, and storage. Undrawn combs do not count as space. Bees in the wild, to generalise, like to have a cavity-sized 40 litres. They are happy with a smaller volume than we give our bees because they want to reproduce.

Wally Shaw recommends putting frames of foundation at the edges of the brood nest in a honey flow. This will encourage them to draw comb. It has not worked for me using plastic frames. I recommend you try using wax foundation. Theoretically, if there is a honey flow, their initial priority is not drawing comb but processing nectar. Once the congestion with nectar is too great, they start drawing comb, so this is the correct timing. Give it a go and watch what happens.

3. Good Bees

The mating of two strains of a plant or animal results in something with “hybrid vigour”. This is true of F1 vegetables and of a bee called a Buckfast. It is gentle and less likely to swarm in its first year. They do not breed true, so new stock must be procured every year or two, which is terrific for queen bee suppliers. Most beekeepers have docile, productive bees that are mongrels, not hybrids.

4. Box under the Brood Box

This is a fiddly caper. It is set up in the Autumn, February, if you are brave. The box contains frames with starter strips interspersed with 3–4 frames of foundation. By maintaining space in the box, the bees do not feel cramped, so they don’t swarm. So in the spring, remove frames before they are completed. My bees tend to draw drone combs, which make lovely supers.

When they build comb in the bottom box it can extend below the frames. Carve this off in the autumn. Otherwise, this technique means disturbing the colony, carving off comb smothered with bees, all when the weather is cool. Once in place, the setup does not need checking until the first inspection.

5. Rotating Brood Boxes

There is a natural tendency for bees to move their brood nest down. It is often believed to be the opposite. Both are true; the brood nest will expand wherever they have the space, usually out and up. It must depend on the time of year. Logically, bees in poly hives should cluster at the top of the hive in the autumn and move downwards in the spring flow to make space for stores. Not so, they cluster more in the bottom than top box. There are few bees visible when you lift the lid. With wooden hives the bees cluster against the crown board so it is possible that the bees move down if they have space, Rotating the boxes creates space for the queen to lay and removes stores that might otherwise cause congestion.

I’ve read that it postpones swarming by two weeks.

6. Spreading the Brood

This takes minimal time. If you like fussing, do it. The concept is that you move one frame (that contains the most brood) to the edge of the brood nest. Hence, the adjacent comb is kept warm, and the queen lays in it. Repeat the manoeuvre every week. Pyramiding is somewhat similar.

7. Equalising Brood between Colonies

By doing this, there is a chance that colonies will do much the same thing simultaneously. Strong colonies will swarm later, and small ones sooner. Big colonies will share their diseases with the little colonies and vice versa. similar. Brood is difficult to chill, but if too much brood is transferred to a weak colony, it may not have enough bees to keep it warm. It is easy to miss seeing Brood in dark comb. When larvae are chilled, brood of all ages goes black/brown/grey. Naturally, check the colonies for disease before you move frames.

As a rule, don’t move more than two frames at a time between colonies.

8. Manipulations

Demaree Vertical Split Vertical Pagden Snelgrove 1

Manipulations that separate the queen from the brood work well. All involve creating a pile, a burger of boxes, with the queen and the brood separated by some supers. With Demaree and Artificial Swarm the foragers move to be with the queen and the brood in the top box results in a strong colony of young bees.

These manipulations keep the colony together and can be used to make increase. Nutrition can be a problem if all the foragers leave the brood, In this instance, give the brood box some honey reserves, sugar syrup and plenty of pollen, perhaps a pollen supplement. If you get it wrong, they produce a generation of small bees. It is widely stated that the bottom box can comprise foundation. Unless there is a strong honey flow, they must have at least three frames of comb for the Q, more if you are using plastic frames. If the queen has no space to lay, the manipulation will fail.

Finding the queen is unnecessary if you do a Shook Swarm, or throw the bees on an plank whose tip touches the hive entrance. Draping an old sheet over the plank makes it easier for the bees. Then shake the bees on the sheet and they obligingly walk in to the hive. They need warm weather.

A split divides a hive in two. Typically, one portion receives more brood, and the portion with the queen receives less.

To do manipulations early in the year, some beekeepers recommend stimulating the colony by giving sugar syrup in March. This may help bees living in wooden hives, but it is a bad idea for colonies in poly hives, which naturally build up rapidly, perhaps too rapidly. Poly hive bees build up so rapidly, that they swarm early. Moreover, feeding in March will be too early for bees living in the North of the UK.

The chief concern is that if they do not use the syrup immediately and the weather becomes cold, they are unable to process it. I don’t know the size of the risk. People say it works. So don’t let me put you off. In the South East, queens have a reasonable chance of mating in May, but not so good in April.

9. Give them a honey flow during the expansion phase

Once a large colony hits the storing season, they are focused on foraging, so swarming is less of an issue (famous last words). But if there is a hiatus in the honey flow, it leaves many foragers bumming around with nothing to do, and worse, this causes congestion of the brood nest. Keenly observe the amount of nectar they are processing. In the June gap, only feed if required, and don’t feed them too much. You don’t want sugar syrup in the supers or your honey will resemble Golden syrup.

10. Chequerboarding

It involves using prolific bees, year one Q, ten frames of stores and at least ten frames of comb—the more, the better—so it requires planning. Rusty Burlew explains why it works. Walt Wright devised this manipulation, and you can read his explanation. Then, you might like to make your brain spin: page 1, page 2, page 3. The frame configuration must be set up during the autumn or winter (nine weeks before apple blossom to prevent swarming in April).

This is the only technique that “guarantees a large harvest” and no swarming if you get it right. But nothing is 100%. Once set up, inspections can be minimal. It is not for beginners. The brood nest will fill three boxes without a queen excluder.

It did not work for me. By April, eleven frames of bees were present in the middle two boxes, with none elsewhere.

11. Disrupt the brood nest / Pyramiding

In a strong colony, sandwich frames without foundation (wooden frames in the photo) between frames of brood. This colony had 17 frames of brood and five queen cups. It still swarmed.

Pyramiding may be advantageous when the bees don’t move up and give themselves some room. It is rather like box rotation. Several brood frames are moved to the top box. The rest go in the bottom box. The bottom box brood frames intermingle with frames of comb. My bees come out of winter on two brood boxes already, so it’s an irrelevance. Perhaps it helps nucs to expand. Randy Burlew explains.

Grey = brood frames, green = comb.

Some beekeepers regard this method as unsound, reasoning that splitting the brood makes a colony more likely to swarm. Considering this, wait until the hive is thronging with bees, by which time they are planning to swarm.

12. Young Queen

Whilst a two-year-old queen may sometimes be a better layer, younger queens output plenty of pheromones and are more vigorous. Running a two-queen hive helps. The Chinese manage seven queens in a hive by removing one of their mandibles..

f you start with a nuc in June, they are unlikely to swarm that year as long as they have ample space and are not too prolific. Then the fun starts:

Received wisdom states that a queen in her first yearly rarely swarms. Mine inevitably swarm unless I split early in the spring. Demaree is currently my favourite method. I have tried Buckfast and other strains, and they swarm. I’ve given them loads of room, and they swarm. I’ve tried most preventative measures and they fail. I suppose it’s me.

Many beekeepers don’t have my problems, or don’t let on if they do.

13. Not using a Queen excluder

Some people claim that a queen stop is a honey stop. If there is a box of honey above the brood boxes, this should act as a QE. However, the Q sometimes lays up through the supers like a chimney. If this happens and I cannot find the queen at harvest time, it makes me feel insecure, and prohibits using clearer boards. Bees find it less of a squeeze to get through some excluders than others. My metal slotted excluders look better than my plastic ones. Before you rush to buy new excluders note that some people say that slotted excluders damage the bees’ wings. I haven’t noticed a problem. Most people use queen excluders and their bees do fine.

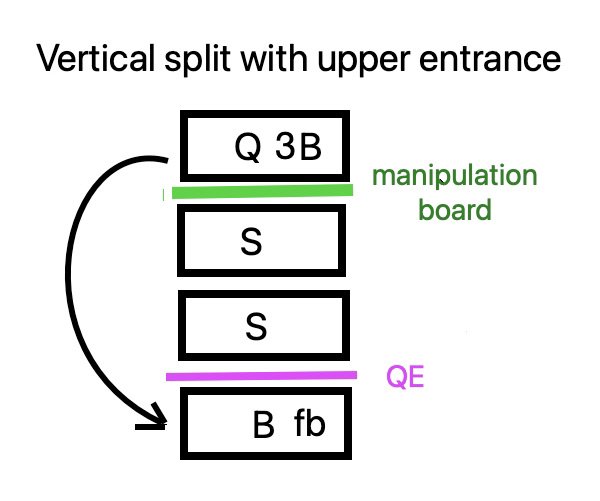

14. Demaree to prevent swarming

Start at least two weeks before your colonies are prone to swarm (do it late March or early April in Surrey)

The Q with drawn comb goes in the bottom box. Alternatively, shake her (and all the bees) in to the bottom box, using an empty box as a funnel; spray its inner surface with water to stop the bees climbing out.

At least two boxes of supers containing comb or foundation go above. Put a QE above and below the supers, or use a QE and a manipulation board above. Up to 4 brood frames can be put in the upper super under the top brood box, but it is vital to remember this at the seven-day check.

Put up to 4 brood frames in the bottom box. This will reduce the power of the manipulation, but may prevent supersedure after the second cycle. Some beekeepers put two frames of brood in the bottom box routinely.

Brood goes up top with plenty of pollen and stores.

Cull the QC in the top box after 6–7 days. Destroy them all if you do not intend to raise a new queen. If you are fastidious, check the bottom box too. Theoretically, they should not raise QC there, but if they do, the manipulation has failed, they are swarming or the Q has died.

If you are using it to raise a new queen. After 8 days, most of the bees have vacated the top box, leaving a skeleton crew of young bees to keep the brood warm. So, it is essential to retain house bees using a manipulation board. Move the QE to mesh after a few days, and open an upper entrance. Done like this, it becomes a vertical Pagden. People worry that if they raise QC in the top box, the queen will swarm. My experience is that they only make 1-2 supersedure QC. If they produce more than three QC, then they should be emergency QC, but could possibly be swarm cells. So destroy them all, or leave one and isolate the top from bottom box, as above.

Repeat the manipulation when there is sufficient brood and if the first attempt to raise a queen failed (which is very likely if you attempted to raise a new queen in April). A new Q can join the original Q separated by a QE, without any introduction method. The new Q boosts QMP, which makes swarming unlikely.

Unless you provide an entrance, drones get trapped up top. If they can’t wait to be released, they prefer to kill themselves by getting their heads stuck in the QE, If they don’t fancy doing that, they die anyway,

Preferably, ensure that you avoid putting some open brood or eggs in the supers.

The colony growth plateaus if it is done too early, with insufficient brood.

It can create a humongous colony that is difficult to manage.

It is prudent, but not necessary, to find the queen.

It results in a high stack of boxes.

If, at the start, they are on the cusp of swarming, you won’t know; if you suspect this you’ll need to kill all the QC in the top box. That’s a standard Demaree.

If the bottom box does not have much drawn comb, the queen will not lay with a bang.

It is not a swarming clamp. Swarm preparations can arise towards the end of the manipulation.

Theoretically, the bottom box may become congested. A queen can fill a box with brood in several weeks. Mine generally lay 5 frames in 3 weeks (they need copious bees and at lest seven frames before I consider repeating the manipulation).

Increased brood can result in dangerous varroa levels.

They may not produce QC in the top box.

A queen reared in April may fail to mate adequately.

To set it up you’ll need space around the hive since it involves making a new brood box, a box for the queen. You’ll need fresh drawn and undrawn comb, stores, box for old comb, brood frames, a manipulation board, and possibly a new floor, and a clean queen excluder.

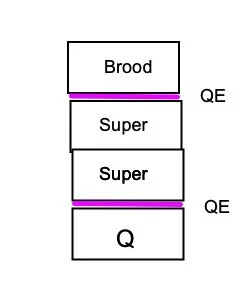

15. Snelgrove method (I) — when no QC are present

Snelgrove and his special board have a mystique surrounding them. Apparently, opening and closing doors are unfathomable, time-consuming, and complicated, so books rarely mention it. In reality, once you understand the principles, it is easy-peasy, Okay, you need a screen board, which is easy to make or buy. The board has three (or four) pairs of entrances, with each couple spanning the board, hence forming upper and lower ones. The manipulation works by sending flying bees from the brood to the box containing the queen.

Start the manipulation by creating a burger of boxes, like for a Demaree. Snelgrove used one super rather than two because he wanted to concentrate the bees to draw out honey sections. I think that using two supers would be more reliable. There is no requirement to cull QC in the top box because, due to lack of foragers, only one queen is permitted to survive.

Snelgrove refers to his board as a screen board (SB) and it has one edge with no entrances, facing forward. My Everyboard has it facing sideways and an entrsnce facing forward. The concern with a front entrance is that bees find there way back to be with the queen. Once the burger is built, the entrance configurations are changed three times (day 3, 7 and 14).

The principle is that to swarm the presence of foragers is required, so by removing them from the brood, swarming is averted. But by doing this, the brood has no foragers to bring it sustenance, so they may need feeding.

Notation

F front

B back

L left

R right

L lower

U upper

S super

B brood

Foraging bees learn their home entrance situation when they do their orientating flights and are loyal to it (see Inkpin Joe effect). So if they leave from a new entrance, they always return to the one that they learnt is home. By changing an upper entrance to its corresponding lower entrance, bees are duped in to entering the bottom box.

The entrance notation is given is for a screen board first and an Everyboard in brackets.

Make a burger in this order (bottom box to top): Queen + one frame of brood, QE, Super, Brood. Do not insert the SB yet. Delay so that the bees can choose their box. QC are less likely to arise if this period is reduced to two days.

After 3 days: insert the SB under the top box, open LU (LU). The existing foragers fly to the bottom box.

Four days later, send the new bees that have started their foraging flights from LU ( LU) to the bottom box by closing LU (LU) and opening LL (LL). Open RU (BU) as a new exit.

Seven days later, open BU ( RU - flip the board), close RU, open RL (BL). BU (RU) is the permanent new entrance for the top colony and the new Q can go out to mate.

My addition: Once the new queen is laying, adjust the entrance in the top box, she can be placed above the bottom brood box separated by a QE.

Notes

A board may be easily constructed out of the plywood boards sold as clearer boards designed for bringing down stores or used as a crown board. The hole in a Porter Bee escape is sufficient; a circular hole 9 cm diameter may be better. Cover the hole with mesh kept in place with drawing pins. Under some circumstances, a fourth set of entrances is handy.

If there are more than eleven frames of brood at the start, donate the excess to another hive. They generate queen cells beginning on the third day or sooner, and since elements like cold weather or lack of food may prevent this, Snelgrove advises that you check that QC are present after seven days.

Later, if there is a honey flow, with a vigorous new Q in the top box, foragers can be used to reinforce the lower colony: use LL (BL) and an upper entrance.

An alternative scheme is to put two frames containing young brood and eggs in the bottom box and put the queen and the rest of the colony above. Reduce QC in the bottom box to one after 7–10 days.

If foragers in the bottom discover that a queen is in the top box, remove the top box to another stand for a few days.

Prevent swarming and make honey

Six things for a good honey crop

Provide space as required

Young queen: A colony with a queen that is one year old is less likely to supersede or swarm.

An early manipulation: before they get the urge to swarm. Without a Demaree, my colonies start swarming in the first week of April. A Pagden or split cannot be done until May. A Demaree can be performed on a warm day in April. Colonies housed in poly hives are up to three times more likely to swarm than those in wooden hives, so don’t wait too long. The Demaree is the magic bullet that has made a huge difference for me. Talk to other beekeepers and they will probably have a winning formula.

Ensure varroa levels are low in the Spring: summary

Wing clipping

Drawn super frames

Page 6.