Life Cycle

Bees, castes and the colony

-

Introduction

1 a. pheromones

1 b. queen

1 c. workers

1 d. house bees

1 e. guards

1f. foragers

1g. waggle dance

1h. drones

1i. swarming

1j. four seasons

2. insect decline

3. insects and humans

-

2.1 able to give an elementary account of the development of queens. workers and drones in the honey bee colony ;

2.2 able to state the periods spent by the female castes and the drone in the four stages of their life (egg, larva, pupa and adult);

2.3 able to name the main local flora from which honey bees gather pollen and nectar;

2.4 able to give a simple definition of nectar and a simple description of how it is collected, brought back to the hive and is converted into honey;

2.5 able to give a simple description of the collection and use of pollen, water and propolis in the honey bee colony;

2.6 able to give an elementary description of the way in which the honey bee colony passes the winter.

Abridged version Queen Workers Drones. Swarming Seasons

If you don’t know an OMF from a runner, look at the naming of parts. If it’s gone gobbledygook, look at the glossary.

Introduction

Unless I indicate otherwise, “bees” refers to honeybees. Bees live in family groups (colonies) of 10-60 thousand, depending on the time of year. They have one queen (Q) whose sole job is to lay eggs. Drones are male bees, and the workers, true to their name, do all the work. Foragers do about ten nectar collecting missions daily. They store nectar in their honey crop and pollen in the baskets on their hind legs. When they arrive back at the hive, the nectar is passed to receiver bees, who carry it to bees whose job is to cure (concentrate) it. Initially, curing involves holding a drop of nectar in their jaws, and subsequently by dropping it in to the comb. It takes a further 1–5 days to reduce the water content to 20%. Foragers rest at night; in other respects, the colony is active 24/7. The wax hexagonal tubes collectively called honeycomb/comb underpins their success. They use comb to store honey (stores) and pollen and to raise their young (brood).

Next, I list some of their capacities:

Teamwork -– the sum of their activity is more significant than their individual contributions. Because of this, they have been dubbed a super-organism. Much like humans.

A large swarm hanging in a tree. The bees bivouac until scout bees find them a nest site. © Crown copyright

Home – They aren't fussy as long as a cavity is large enough with a small entrance. In nature, they live in cavities in trees and rocks (and holes in houses), but we trap them in hives. Bees often abscond from an empty hive unless they have chosen it. But if we stop the queen from leaving for a few days, she lays some eggs, and the workers will not abandon them, so they call their hive home.

Communication: Bees communicate through dances, food, scents, and vibrations. These enable a colony to respond to threats and coordinate its activities effectively.

Resilience: In 1992 the varroa mite arrived in the UK and devastated honeybees. However, beekeepers soon learnt to control it. Now varroa-resistant bees are becoming common. Many people have heard that honeybees are in trouble. Not so. Other bees are.

Reproduction: Like all creatures, reproduction dictates their pattern of life. Bees do this by swarming; 50-75% of the bees leave their home with the Q and form a new colony. After this, the home colony makes a new queen, and both colonies rush to store enough food to get through the winter.

Winter: During the winter, they survive by clustering together for warmth and living off their honey stores. In the spring, they build up rapidly to swarm again.

The Colony

Basic Assessment: identify the female castes and drones & the difference between drone, worker and honey cappings.

A honeybee (Apis mellifera) colony consists of 10 to 60,000 bees, depending on the time of year. Like ants and termites, honey bees are social insects because they work together as a big family. They are motivated to do so because they share their genes in an interesting way.

1a. Communication – Pheromones

Pheromones are scents that bees use to communicate widely. There are two types: releasers and primers, depending on whether they have a long-lasting or more transient local effects. Contrast them with more individual communication via body language and vibrations.

Pheromone messages sometimes contain a complex mix of chemicals and are often transmitted by sharing food. For example, the Queen Mandibular pheromone (QMP) is a mixture of 5 chemicals, and by adding four more, the combination forms the Queen Retinue Pheromone. The mix of the substances mediates the message. Whereas, the only pheromones that dogs understand are “I want to hump” and “Your butt smells nice” (I jest).

QMP has many effects. Beekeepers are most concerned about its role in swarming. If the Q becomes old or her fecundity falls, her pheromone called QMP reduces, and they swarm.

The QMP level drops when the queen is lost. Within 15 minutes, the whole colony appreciates it. Some bees scurry around, searching for her. This is not a temporary effect. Their running behaviour (QMB) continues until they get a replacement queen; The presence of queen cells (QC) doesn’t affect it.

A colony is in a state of dynamic equilibrium as the bees rub against each other like the eddies in a stream, and the mix of pheromones in the hive ebbs and flows. For example, if one part of the system flounders, maybe many larvae die, the brood pheromone levels fall, consequently the queen is fed more, and her rate of lay increases.

If house bees die, the larval brood pheromone called E-β-ocimene, which regulates the activities of workers, including the nurse-to-forager ratio, will power up some forager’s pharyngeal (salivary) glands to feed the brood.

Another example is that foragers share a pheromone with the receiver bees when they unload their nectar load. If a forager spends much time finding a receiver for their nectar, she does a tremble dance, which recruits more receiver bees. Hence, the super-organism is aware of the amount of nectar coming in, which determines the division of labour in the colony. There is no leader in a colony; control is decentralised.

More about pheromones – Smithsonian Institute

Communication – Body Language, antennae, and vibrations

On the micro level, the actions of one bee cause others to react and vice versa, so before we disturb them, they are doing something meaningful. Individual bees can indicate things like danger, attack, “come here”, nectar source depleted, danger at nectar source, and this is the direction, distance to some flowers which produce this amount of nectar and which have this scent. By exchanging food mixed with pheromones (trophallaxis), a message can be communicated through the colony surprisingly quickly – in minutes.

Bees’ antennae are bristling with sensors, including CO2 and magnetic field detectors. Touch sensors detect air movement which, for example, enable them to orientate their bodies for trophallaxis (sharing pheromones as they share food). When bees touch their antennae, they receive information; they do not have a conversation (except “I’m here”), which I find disappointing. Since their eyesight is poor and they have to spend a lot of their lives in the dark, their antennae are like sensory walking sticks.

Note how her antennae are placed down in the water as she drinks.

The bee in the background is a guard rising in a menacing ”crab” posture with open mandibles.

To appreciate the action increase the video to full screan. Run it twice; look at their legs first, and their antennae next. Bees do a lot a split second.

Somewhere between pheromones and body language are vibrations that transmit information an intermediate distance. After a colony has swarmed, further queen(s) emerge, and they make vibrations called piping. Their duet signals to the workers whether to send off another swarm. I believe the traditional view of piping has been discredited. It was believed that piping is a war-cry between queens.

1b. The Queen

A Queen’s lifecycle = three days as an egg + 5 days as a larva + 8 days as a pupa + 9 days mating and preparing to lay, and 1 - 4 years laying eggs.

Queen laying an egg whilst workers caress her.

The Queen’s genes and how much the workers feed her determine how prolific or cautious the colony behaves. Whether she produces loads of workers early in the year in expectation of a bumper crop or takes care in case of poor weather, the first characterises an Italian bee, and the latter a Dark British bee.

Her distinctive features are that her body is larger than other bees (19 mm long), her dorsal thorax is dark, large, and domed, and her abdomen protrudes beyond her wings. Her long legs are difficult to appreciate.

Queen Development

Formation of Queen cells (QC).

When an egg destined to become a Q “hatches” (really, bee larvae absorb their casing rather than hatch), the workers extend the walls around the cell to form a QC. Inside this, the larva floats on a pool of nutritious, white, royal jelly. Decent queens only arise from larvae that have received optimal nutrition. More about QC

After five days, the cell is capped with wax and the larva spins a cocoon. A mature QC looks like an unshelled peanut.

Photo: Queen cells — about two days old.

To one side of them is an area of sealed worker brood (pupating workers).

After eight days pupating, the Q emerges from her cell, matures and mates over the next 1–5 days. Bees go to mate in precise areas that are dotted around the landscape. They are called drone congregation areas. Drones (males) go to the nearest area, whereas queens often fly further away to avoid mating with their sons. They may fly several miles.

Soon after mating, queens start laying. Occasionally, it takes four weeks for a perfectly good queen to do so. More pictures of queen cells.

On average, she mates with 12 drones, each of whom inseminates her with 100 million sperm. Since she can only store 6 million sperm, she has a bit of sorting to do! She shuffles the sperm unevenly, making some genotypes more common than others. The sperm derived from the queen’s mating plays a significant role in the colony's functioning; each drone’s sperm results in a kinship (patrilineal) group. For example, if the Q mates with 12 drones, there are 12 genetically different worker groups. Each group adds richness to the way the colony functions. For example, the groups may have different temperature thresholds to start fanning. They are like a football team, where each position has different expertise. Some are better at scoring goals, others at saving them, but they all kick the ball. So, the colony is more robust the more drones the Q mates with; she needs to mate with at least seven; otherwise, the colony will replace her. The weight of a queen is a good surrogate marker of her quality. The appearance of the queen’s abdomen reflects this. Workers show little attention to a virgin queen, and the most attention to a queen who has mated with plenty of drones.

Once a swarm or colony settles in a nest cavity, the bees draw some comb so that the Q starts laying almost immediately. You might have thought she would get bored perpetually laying eggs. Fortunately, she is not the brightest of bees. In the latter part of her pupation, she suffers massive brain cell death at a stage when workers are growing more brain tissue.

Making good queens requires loads of nursery bees, pollen, sugar, and little competition for food from unsealed brood. A poor Q has a small abdomen. A really poor Q may only lay a few eggs or initially lays with gusto but soon falters. Ultimately she will be superceded (replaced without swarming). Swarm and supercedure cells generally make the best queens.

Laying eggs

Queens measure the size of each cell with their hind legs (and possibly, her middle legs). She does not fertilise the egg if it is a large drone-sized cell, but does so if it is a smaller worker-sized cell. If she runs out of sperm, she lays unfertilised eggs in worker cells. These grow into drones. In the spring build-up, her maximal egg laying rate is 1500 (possibly 2000) per day. Other people say that she measures each cell using her front legs and even her head and spins around to lay her egg. I cannot recall where I learnt about rear legs, but I do know that I’ve never seen spinning queens.

Queens can live for four years, but most beekeepers cull them after 1-2 years. This is because something toxic in our environment makes them more likely to swarm, disappear, or fail. The risk is lower with vigorous young queens.

Queen failure

When a queen runs out of sperm she can only lay unfertilised eggs which grow into drones. When she dies or is lost, bees act in a characteristic way.

1c. Workers

The worker lifecycle: 3 days as an egg + 6 days as larva + 12 days pupating + 21 days as house bee, + an average of 21 days foraging. During the winter they live for five months.

Workers are female like the Q, but after they hatch, they are only fed rich food for three days, and their subsequent diet (and exposure to pheromones) suppresses their femininity. They are 12 mm long.

A sad bee - has she lost an antenna? No, it’s an end on view. Bees use antennae to sense their world.

More about bee antennae - Rusty Burlew

Video - bee development - from National Geographic

1d.House bees

Newly emerged bees look small and grey and cannot fly or sting; they help keep the brood warm and do menial tasks for several days. After this, they graduate to prepare cells for the Q and then to look after the brood. Their tasks progress in line with their glandular development. So, in the first six days, the bees’ hypopharyngeal (salivary) glands develop. Consequentially, they can feed larvae. Since they consume honey and pollen, they progress to feeding older larvae. Food stimulates their wax-making glands and, finally, their stingers.

In this stage of their lives, they live in complete darkness and may navigate by appreciating the characteristics of each frame. When we move their combs around, it disorients them.

Middle-aged bees can multitask and perform various jobs at the same age, such as feeding brood, receiving nectar, packing pollen, and ventilating. However, they are more adept at doing one particular job at a specific age. Crucially, bees aged between 1 and 11 feed the Q, and ones between 4 and 17 days old look after larvae and can produce wax. Older house bees cannot do these tasks because they are preparing to become flying bees, and their pharyngeal glands are shrinking.

Sometimes, as many as 30 - 40% of house bees remain inactive or wander around to help with whatever process needs them. For example, some join the heater bees that warm the brood nest.

Other bees fan with their wings, and by controlling the airflow pattern, they adjust the humidity, carbon dioxide levels, and evaporation of water from nectar and, if necessary, they cool the hive interior.

The temperature in the brood nest must be precisely 35 deg.C (plus/minus 0.5 degrees) for the brood to grow into the best bees. A colony (even in a wooden hive) can survive temperatures over 40 deg.C, but only if it has access to water.

Young bees cluster over the brood to keep it warm (honey stores are at each end). This effect is most visible with the Demaree manipulation when the young bees care for the sealed brood in the top box. These little bees stay in position rather than mill around.

Orientation and pre-foraging flights

Orientation flights: Whilst still house bees, workers make tentative forays outside, doing short flights, learning the position of the hive. Orientating bees usually fly in small groups, facing the hive, and form a noisy little cloud. Their dance is a bit circular; combined with bounces, as if they are hit by air currents. The dance ends as abruptly as it began, but some bees go on to fly in widening circles high above their hive.

There are typically no cues on the front of the hive to suggest that their dance has anything to do with learning its appearance. But, they may be learning the position of the hive relative to the sun. Additionally, they have iron deposits in their abdomen and at the base of their antennae. These magnetic sensors could be related to the sun’s position. When they circle high above their hive, perhaps this more for learning the appearance of visual features in the landscape. For more information, visit the Apiarist.

As they transition to being foragers, they perform pre-foraging flights: they fly ever longer distances from the hive to construct an impression, some sort of map of the area. They achieve this by combining two senses - heat and vision.

Worker brood

Basic Assessment: Identify brood at all stages

The Q lays eggs in a circumscribed area called the brood nest. It is usually situated in the centre of the hive where temperature is best regulated. The maturity of the brood has a pattern. The Q first lays eggs in the middle of the comb and then successively lays eggs in bands around it, like the rings of an onion. The youngest larvae in the photo are roughly early day two. Open/uncapped/unsealed brood is the beekeeper’s term for larvae and eggs.

A comb containing eggs (it is referred to as a frame of brood or a frame of eggs).

When one tranche of brood has emerged, young bees prepare the comb for the queen

The small areas of pallor between the bands of sealed brood (first photo) are due to open brood. If there is a surplus of stores, the bees place them on the edge of the brood. In this way, it is near the open brood that needs feeding. The lower picture demonstrates this. There is a band of orange pollen around the brood and honeycombs in the upper corners. Basic Assessment - identify stored nectar, honey and pollen.

In a hive where they live in two hive boxes, the nest occasionally spans the gap with an oval brood pattern as in the first photo, but it is usually contained in a single frame, as in the second photo.

As the brood nest expands, they use the pollen on neighbouring frames, making more space for the queen to lay. When the colony is populous, they start placing stores at the corners of the nest. Stores in this position block upward expansion and can signify that they are ready to swarm. They are reluctant to move honey from mature honeycomb, so they keep it at the periphery of the nest (and so should you). The honey is kept for an emergency, when there is a lack of nectar (dearth), but is unpopular with beekeepers as it causes less space for the queen to lay and contributes to congestion. So, if it is cramping the brood nest, move it up the hive and replace it with comb.

1e. Guards

On the cusp of being a forager, a few bees become guards, although which bees are doing this at any time is quite fluid.

Guard bee monitor incoming bees. They usually attack bees from other colonies but accept bribes. If a foreign bee acts submissively and offers some nectar, she will be admitted.

A bee is a guard for one day, more or less. When I say guard, there is a massive variation in how they behave. One colony is chilled, while guards from another hurl themselves at you when you are 10 meters away.

Attacking an imposter

Guard bees stay close to the entrance and communicate threats to the rest of the colony. By extruding their stingers and fanning their wings, they can blow a mixture of pheromones (15 active substances) into the hive. Isopentyl acetate is important. It smells like cellulose thinners or ripe bananas. You already know that the bees are severely upset when you smell it (I’ve sniffed it once, and I hope you never do).

Smoke repels bees, knocks out their ability to sense alarm pheromones, and stimulates them to gorge on honey. Bees with tummies full of honey find it more difficult to bend their abdomens to sting.

If a colony is repeatedly mistreated, long-acting internal changes via immediate gene expression can make them persistently defensive, so treat your bees with care!

Navigation and drifting

Once they have graduated from pre-foraging, a bee can navigate more accurately than GPS. But they can get it wrong, particularly if all the hives look identical. So, drifting to the wrong hive is expected when the hives are situated a few feet apart and all facing the same direction. As many as 4% of foragers end up in the wrong hive every week, and potentially 7% of queens go astray when they go to mate.

When a colony fails to thrive, it may be a drifting issue, not a colony issue. The richness of the landscape (Items like trees and shrubs) and crosswinds influence drifting. If hives are dotted around the apiary, it is less common. Simple patterns painted on the box above the entrance assist them more than bright box colours. Their maximal visual sensitivities are ultraviolet, blue, and green. Bees perceive red as black and barely see yellow.

They navigate by the sun, magnetoreception and by internalising a monochrome memory of the features in the landscape. Bees estimate distance using “optic flow,” i.e. the faster features go past, the further I’m going. Initially, foragers are attracted to flowers by scent. When they get around one meter from their targets, they activate their colour vision and see blobs of colour. At 30 cm, the flowers become visible.

Insects have compound eyes, meaning the image they perceive is pixelated, like a stained-glass window where each little pane contributes to the whole picture. Despite each bee’s eye comprising only 2,500 pixels, they are good at detecting contrast. Insects have different needs from mammals. They must respond rapidly and watch for danger (so their eyes can see almost 360 degrees). Generally, they don’t need to see fine detail. In addition to their large eyes, bees have three weenie eyes on the top of their head, which help them navigate.

1f. Foragers

Graph 1.

House bees lose 42% of their body mass (research) to be efficient flyers; their weight falls to 90mg.

A forager can carry 40mg of nectar in their honey crop. Pollen collectors carry a 7.9mg pellets of pollen (mixed with nectar) in each honey basket.

It is commonly believed that foragers live for 21 days and die when worn out. This is a gross approximation. Some bees and colonies are fitter than others, and bees get lost and are predated. During the active season, foragers do live an average of 21 days, but their longevity varies with a standard deviation of 14. The standard deviation indicates the spread of ages. Some survive over 36 days, but many live less than 8. Sometimes, heavy casualties occur in the pre-foraging phase when they learn the topography as illustrated in graph 1 & 2. Following this, foragers continue to die by gradual attrition. If most bees died when they were worn out, many bees with tattered wings would be visible in the hive, but there are extremely few.

Alberto Prado et al (2020) Cumulative survival (see graph 1.). 40 - 70% of flying bees died in the first 5 days. The duration of a bee’s pre-foraging phase has a positive effect on her longevity:

“The age at the onset of foraging is the central variable in worker life-history and behavioural state and was found more important than chronological age for honey bee ageing.” Rueddell. O (2007).

The lifespan of bees can vary between colonies.

Graph 2. from a study in Ohio (2022) shows the mortality of bees in paired hive locales. M stands for managed, and F stands for feral colonies. In this study, bees from feral colonies lived significantly longer.

Graph 2.

Foraging and the super-organism

Full polllen sacks

Resin is usually collected from Poplars, Ash, Chestnut or coniferous trees. In this case resin has oozed from a Beech tree.

Basic Assessment: able to give a simple definition of nectar and a simple description of how it is collected, brought back to the hive, and converted into honey. Foragers collect four things: resin, nectar, pollen and water. Pollen is for protein and fat, nectar is for carbohydrates, and water is for diluting honey or cooling the hive.

Resin (derived from dried tree sap and sticky buds) is the chief component of Propolis. Resin is sticky so it’s impressive that bees transport it in their corbiclulae (pollen sacs). It is the chief component of propolis. Propolis is made by mixing resin with spit and wax. It is gooey above 19 °C and sets solid at lower temperatures. It is used for sanitisation, to fill small gaps, and create “walls” so for example, they use it to reduce the size of their nest entrance . As an antiseptic it is used to the line the rough walls of nest cavities, and coat brood cells. Whilst it is not stored it is recycled.

Resin was so valued by the Romans that theft was punishable by death.

Nectar collectors do about ten nectar missions daily. When they arrive back at the hive, nectar is passed on to receiver bees who cure (concentrate) it, initially by holding a drop in their jaws. Then they dump it in the comb, where it takes a further 1 - 5 days to evaporate the water content to 20%.

Bees obtain pollen by raking it off their bodies using their legs and mix it with nectar to give the consistency such that it stays in their corbiculae when flying, and remains easy to remove.

Every day, each forager specialises in what they collect and from what source they obtain it. So, for example, in a field of yellow and blue flowers, one bee will exclusively visit the blue flower, whilst another will exclusively work the yellow ones. Similarly, one bee will exclusively visit one fruit tree until the nectar is exhausted before moving to a neighbouring tree. It is their loyalty to one crop that makes honey bees such valuable pollinators.

Some foragers specialise in pollen collection and can bring in their load more quickly than nectar collectors. So pollen collectors often swap to foraging for nectar later in the day. Pollen collectors make a round trip in about 30 minutes, whereas a nectar collector can visit as many as 1000 flowers, taking 2–3 hours. More about foraging:

Another bee ability is great plasticity. For example, if the colony loses numerous mature foragers (e.g. from a pesticide), young bees are promoted to replace them, but they soon die because to fly efficiently, they must lose weight and orientate; they cannot do this overnight. If many young bees change role, there will be insufficient nurse bees, which can have a catastrophic effect on the colony.

Should experienced foraging bees be needed to boost nurse bee numbers, they are similarly inefficient as their hypopharyngeal glands have shrunk.

The worker population depends on the rate of production versus attrition. The graph below explains all, Refer to Scientific Beekeeping for a full explanation.

Seasonal demographics of a colony headed by a vigorous young queen, shed wintered in Manitoba. Each band of color represents the proportion of bees in each 12-day age class at any time point. Red (0-12 days of age) through green (61-72 days) age cohorts represent short-lived “summer bees,” which rarely live longer than two months. The blue and violet age classes are the long-lived “winter” (diutinus) bees that hold down the fort when there is no incoming pollen (and thus little recruitment). The dotted line represents the number of cells of brood. The numbers along the x axis represent the average age of all bees in the hive at any time point. The pattern is quite similar to that of colonies in England.

An experienced forager with tattered wings

Predation

A Crab spider

A few days later the spider had colour shifted.

If a forager finds danger at the nectar source, like a dead bee, when she returns home, she gives a vibrational signal and headbutts a dancing bee, asking her to stop.

Nectar

Basic assessment: able to give a simple definition of nectar and a simple description of how it is

collected, brought back to the hive and converted into honey

Nectar / dilute honey / dilute sugar syrup are a bee’s equivalent of cash. They are for immediate use. Honey is like money in their savings account (before the introduction of online banking). That’s an important distinction.

These days, the bees in many rural areas have only a few significant nectar sources.

Different flowers produce nectar at varying times of the day. For example, Oil Seed Rape (OSR) yields more in the morning and clovers more in the afternoon. Each flower has idiosyncratic nectar in terms of sucrose-glucose-fructose proportions. The usual concentration of sugar is between 20 and 40% but sometimes lower, like Pear (10%) or higher, like Dandelions (50%).

Pollen sources are sometimes different from flowers that provide good nectar. For example, spring pollen sources are crocuses, pussy willow, and hazel.

You may be interested to see:

Pictures of flowers for bees

How different nectars determine the sugar balance of honey

The photo shows the rear side of the Beekeeper’s Rule — sold by Thorne. The other side is a brood calendar.

You’re amazing! You got this far. You deserve a knighthood. Have a break!

Bees naturally go for the most concentrated nectar sources, which can cause problems for farmers. For example, dandelions are more attractive than fruit blossoms.

Another issue is that flowers produce little nectar in prolonged dry weather; a lack of nectar is called a dearth. A good source of nectar is called a honey/nectar flow. A colony may starve during a dearth, particularly when rapidly building up, i.e., March to June.

Honeydew is “nectar” obtained from aphids. When aphids pierce a plant’s vein, the pressure is so high that it forces a sugary solution out of their anus. This syrup results in dark honey.

A field of mustard — a good source of nectar

The Waggle Dance

There is no need to know about this. But it is famous. If you prefer, skip to the section about drones.

Foragers generally don’t just fly willy-nilly to find some flowers; scouts ordain 40–90 % of flights. These scout bees fly out early in the morning. If they find a good source of nectar, they tell the bees back in the hive, awaiting their work schedule.

It works like this: the scout flies back and forth between the hive and the flowers up to 10 times before starting her dance. During this process, she learns the direction and flight distance (not the direct distance) to the nectar source. Once confident, she lets other bees know by dancing on the frames.

She communicates using a waggle dance. Please refer to Figure 1. line (A) indicates the flight distance (including detours) and the quality of the source by the vigorousness of her waggling abdomen (W). Also, it indicates the correct angle from where the sunbeams transect the horizon to the nectar source (A) i.e. the azimuth. She alternates her return journeys between (R2) and (R1). So she runs up (A), turns left to (R2), and up (A) again, only to take the right-hand fork (R1) for her return journey (why this R1, R2 pattern?).

She dances upwards if the source of nectar is in front of the hive entrance and downwards if it is behind. Bees already familiar with the geography of the area she describes are more likely to be recruited. Once recruited, individual bees may make several sorties before they find the target. But the dance is sufficiently accurate for the colony to reduce the inefficiency of every bee having to expend her effort finding a source of nectar. The flip side of this capacity is that they are so efficient that they can suck up all the nectar in an area leaving nothing for other pollinators that live in the same ecological niche.

Waggling in the dark

The foragers have to “feel” the dance in total darkness. They stand around the dancer, picking up her motion with their antennae. They may follow her movements.

Figure 1. The pattern of the waggle dance

Watch a Video of a dancing bee

Decoding the waggle dance

Researchers have decoded it so accurately that they can learn where bees are foraging. But they need a high-speed camera to catch the action as the dances don’t last long. If the dancer dances again, sometime later, she will adjust her dance to take account of the change in the sun’s position; bees have a sense of time.

Of course, the success of the dance depends on the capacity of the followers. For example, an experienced forager may find the source in four minutes, whereas an inexperienced bee takes 40.

If you can’t quite grasp the waggle dance try this:

When following the dance, bees innately know that what happens in the vertical plane relative to gravity corresponds to where the sun strikes the horizon. So a forager watches the dance and remembers the angle X. When she leaves the hive she applies X relative to the position where sunbeams strike the horizon.

Figure 1. is what the bee perceives. Figure 2. shows how a bee reacts when looking from above.

The dance has limitations; it lacks accuracy. Some have suggested that the guide bee flies to the nectar source and fans Nasonov pheromone, calling, “Come here.” I’m not sure about flowers, but they definitely do it to advertise a water source.

Basic Assessment: identify the female castes and drones & the difference between drone, worker, and honey cappings

1h. Drones

Three days as an egg + 7 as larva, + 14 days pupating, + 15 days preparing to fly + 34–55 days flying = 94 days

From a genetic perspective, males have only one of each set of chromosomes; they are haploid. This is what makes them male. They are layabout sex machines who are slow to grow up. Drones are fed by workers for the first ten days of their adult lives and take two weeks to mature. Only when a colony has enough nectar coming in do they produce drones. So, the number in a colony varies from none to many thousands. In the autumn, they become superfluous and are expelled from the hive.

Sealed drone brood. The cells are larger than worker brood and more domed.

Drones are helpful in cold weather when they help keep the colony warm, but that is it; they wander around feeling important. Drones are generally unpopular with beekeepers as the parasite, varroa, breeds well in drone brood.

Whatever the race of the bee, drones have broad abdomens, furry brown/grey thorax, huge inky black eyes and are 15 mm long. Their abdomens vary from gunmetal grey to yellow/brown stripes like their sisters.

Their gigantic eyes are to see queens, and their broad thorax houses powerful flight muscles. They have no stinger.

Drone Congregation Areas (DCA) mating lek

On a summer afternoon, in fine weather, an astonishing number of drones 8 - 15,000, sometimes many more, fly to a mating lek hoping to find a queen and mate.

Few drones manage to mate. If they copulate, their penis is ripped off and they die. The remains of their penis is called a call sign and is coloured so that another drone finds the Q more easily.

A worker fueling a drone

1i. Swarming

Basic Assessment: Give an elementary description of swarming

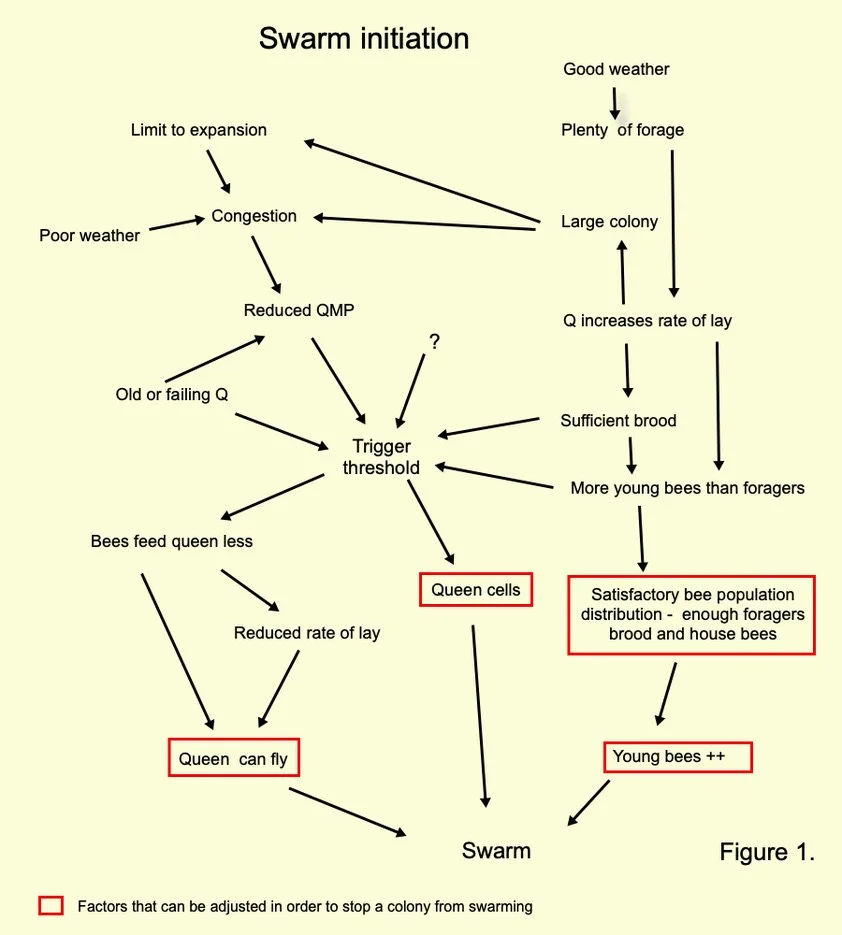

The initiation of swarming is not fully understood despite a large body of research.

Queen mandibular hormone (QMP) is important. A low-level reduces colony cohesion.

A. change in the ratio of young to foraging bees

The queen is fed less so that she loses weight.

Her rate of egg laying falls precipitously 5–7 days before the swarm.

The brood nest area reduces (due to encroaching stores), which leads to congestion and less brood.

Since the Q walks less far, her tarsal (foot) pheromones appear low to many bees (and since the Q does not walk on the bottom of frames, queen cells tend to form there).

Swarming can occur without premonition.

Swarming can occur anytime in the active season. Usually before July but can occur as late as September. The bees start their swarm trajectory several weeks before making QC, There are few if any signs to indicate their intent.

Within a day or so of a queen cell being sealed, the swarm leaves. The old queen is accompanied primarily by young bees, some of whom have never been outside the hive. 50-75% of the colony accompanies her.

The queen and cloud of bees (the swarm) fly out and cluster (the cluster is also called a swarm) in a tree, on a post, in a hedge or something similar nearby. They bivouac until scout bees, about 100-200 of them, find a new home. But some small swarms (casts—with a virgin Q) leave the hive without stopping.

Scouts dance on the surface of the swarm to let other scouts know about a site they have discovered; in this way, others check it out. When a bee surveys a potential site, she crawls around, clocking up 50 metres. Scouts advertising less favourable sites gradually stop dancing. Finally, they all dance the same dance. They’ve come to a decision. It may take them more than a couple of days to achieve consensus, so if there is bad weather, the swarm can become exhausted and drop to the ground.

When the scouts are ready to direct the swarm to the new nest site, they go through the swarm, giving the “warm your muscles up” signal; then, the “take off” signal, and up they go. The swarm looks like a large cloud of gnats. The scouts direct the swarm by performing a sequence of high-velocity flights through the upper swarm.

As soon as they enter the new nest cavity, they create a milieu suitable for drawing wax and caring for their brood. This means that stopping drafts is a priority. Propolis is used to fill small cracks and line the cavity. It can set as hard as two part wood filler; Beekeepers regard it as a nuisance as it makes the frame lugs sticky.

Somehow, the swarm forgets about the home colony. But if you immediately remove the swarm and throw it on the ground, the bees return.

Secondary Swarms

After the first (prime) swarm has departed. There is an interlude, before further queens emerge and form secondary (post prime) swarms. This process is regulated by vibrations called “piping”. It is a dialogue between emerged and captive queens. The workers are the audience.

Bees’ antennae are bristling with sensors

Chemical, magnetic, movement, temperature, touch, and carbon dioxide.

The home colony after the swarm

This is a nice queen cell with large sealed drone brood cells nearby and a small area of sealed worker brood in the distance. Some drone cells are protruding more than usual because they derive from unfertilised eggs that have been laid in worker cells. More than a few indicate that the queen is failing.

Seven days after the swarm, the new queen emerges from her QC and mates at a DCA (with a success rate greater than 95% where I live, poorer in other places). Her colony gathers enough honey to see them through the winter.

The prospects of a swarm that a beekeeper does not rescue are poor. There is a lack of natural nesting sites; they may have to replace the old queen.

The following spring, the cycle is repeated. Colonies build up to swarm and be ready for the honey flow in June/July. In some areas, their overwintering success depends on gathering nectar in two months. Even so, some colonies swarm at peak honey harvest.

Wax production

Wax plates are produced from structures on their ventral abdomen. First, bees gorge themselves on honey and then hang in position for 24 hours.

Building comb takes a lot of energy - 7 lb of sugar per 1 lb (0.45 kg) of wax; about 4 Kg per box of frames. Since a bee usually only makes wax for 3–4 days of her life only the strongest and lucky swarms survive in the wild, about 1 in 4.

For more information: swarming

Wild comb. The bees decided to build comb upwards rather than downwards, something I’ve never seen before. The largest comb keeled over.

1j. What bees do in each season

Bees have three seasons rather than four

Expansion and reproduction

Colony growth begins in February, when the Q starts laying a significant number of eggs, preparing the colony for swarming or the spring nectar flow. March is critical, as they have more brood than bees and may run out of stores.

Swarming. Colony reproduction. Preparation starts three weeks before any signs show.

Preparing for winter

They race to collect enough honey and pollen to get them through the winter. Drones become superfluous and are dragged out of the hive and left to die.

Overwintering

Bees cluster for warmth and live off their honey stores

A Drone in the winter

An occasional drone survives the autumn exodus. I suspect it happens because they emerge after the majority of adult drones are pushed out. The picture shows a drone in mid-January. He was making some pathetic orientation flights. The photo also shows how bees like to nibble polystyrene.

Insect decline and threats to pollinators

Fungicides adversely affect bees.

Populations of wild pollinators like solitary bees and hoverflies are in steep decline. Research in Germany observed a 76-82% decline in flying insects in protected areas over the past 27 years.

Observations of invertebrates in corn fields by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust made over a 50-year period showed a drop in overall insect abundance of 37%. They recommend changes to agricultural practices that will, for example, double the number of songbirds without loss of productivity. I’m impressed that anything other crops live in intensively cultivated arable land.

Pesticides and fungicides readily contaminate pollen. Even parts per million can make a difference. However, the achievement of (almost) banning neonicotinoid pesticides is an example of what can be achieved. Despite these threats honey bees thrive in most of England. Hopefully, the government’s environmental initiatives will make a difference.

Growing bee-friendly flowers in your garden is a good idea—every little helps. Different pollinators are attracted to different style flowers. For example, bumble bees are suited to tubular flowers because they have long tongues. Honey bees are generalists with 7 mm tongues (which makes mediumish long-tongued bees). Look on YouTube.

It's a great film that depicts interaction and complex interdependence. The film must be made on the continent. Wildflower meadows are almost extinct in the UK.

Competition with other bees

A Bumblebee and a solitary bee love each other.

“The effect of reducing the quality of the available habitat (for bumble bees) is exacerbated by increased competition, for example, with kept honeybees or commercially reared bumble bees.”

Two species of Bumble Bee went extinct in the 20th century. Currently there are eight (out of 25) seriously at risk.

Resource overlap

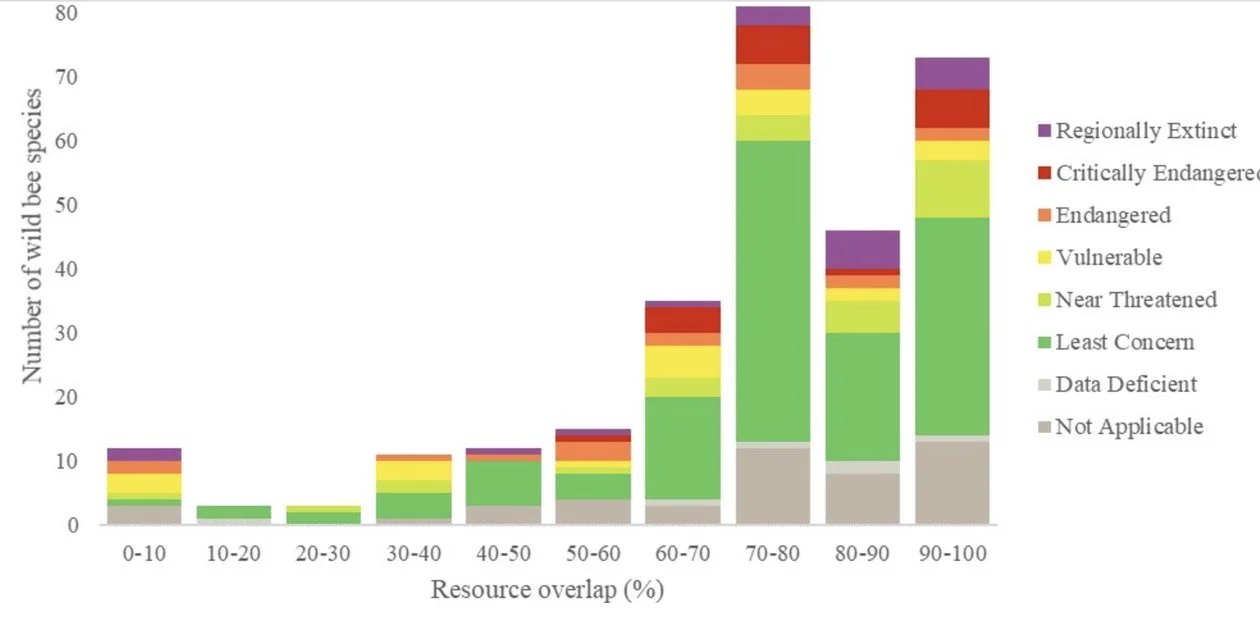

Consider an analysis in Denmark of resource overlap between honey bees and wild bees (292 species). One hundred eighteen plant genera were only visited by honey bees and not by wild bees, and 116 plant genera were only known to be visited by wild bees. This leaves 176 plant genera where a foraging overlap occurred between honey bees and wild bee species. Greater than 90% overlap occurred with 11 threatened species. Wild bees tend to visit fewer plant genera, which reduces competition between species. But honey bees are generalists and act like a bull in a china shop.

The graph shows how resource overlap predominates. This is true for most endangered species (red/orange). Other studies indicate that honey bees do displace wild bees. “Until we fully understand the complex interactions between managed honey bees and threatened wild bee species, it would seem prudent to use the precautionary principle and avoid placing honey bee hives in places close to known or suspected populations of threatened bee species during their active season.”

3. Human attitudes towards wasps and bees

In Lubbock’s seminal work “Ants, Bees and Wasps,” (a Victorian Top of the Pops) he recalls how he befriended a queen wasp from the Pyrenees. They were companions for eight months until she died. She stayed in a bottle during a trip to Russia, and he would let her out occasionally to feed off the palm of his hand. When she had finished, she would return to the bottle!

Initially, she had her stinger at the ready when there was a disturbance, like when the ticket collector came, but she soon relaxed and permitted Lubbock to stroke her. He wrote as she died, “She could but move her tail, a last token as I could almost fancy of gratitude and affection.”

What a relationship with an insect!

People have expressed their view of bees and regarded them as a good model for humans because of their industriousness. The queen was mistaken for a king, and the eggs were produced by immaculate conception.

More recently, they were said to be “quite a model community for they respect their queen and kill their unemployed.”

A contemporary belief is that there is an 80% likelihood that honey bees are sentient.

Many people probably regard insects as unpleasant things that sting. But we can use our bees to help people reconnect with nature. Members of my association go into schools to enthuse about bees, which seems an excellent place to start. The children and teachers have a good time.

Next up - Seasonal guide

Supermarket billboard advertising pesticides

2.