Temperature & damp

Everyone accepts that damp kills bees, but very few deal with the cause.

Colonies in wooden hives die. Whereas beekeepers using poly hives, in the same environment, barely ever lose a colony. The contrast is stark. Beekeepers using wooden hives routinely suffer 18% - 30% - 50% winter losses, (UK and Canada West Coast, USA respectively). Usually, there is no obvious reason for losses. The American situation is different as commercial beekeepers take their colonies South to over-winter and colony collapse syndrome is an issue.

I cover the general differences between poly and wooden hives here:

As far as I know, here are no studies where one factor under investigated is changed whilst taking account off / controlling the others. When comparing poly with with wooden the obvious discrepancy is damp and insulation. But, for instance, when it rains we use umbrellas, umbrellas don’t cause rain.

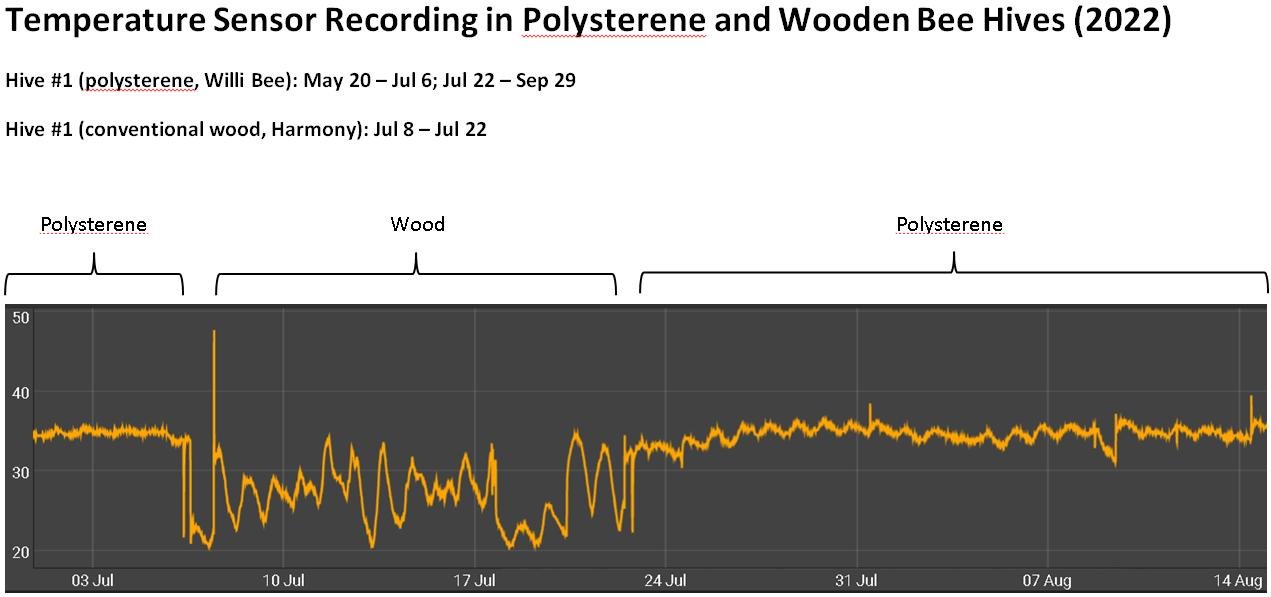

This temperature graph demonstrates temperatures in different hive types. The brood temperature is maintained at 35 °C in both hives. This requires less extra work for bees living in poly hives. It is like cycling on the flat.

Preventing winter losses

Not all humidity and cold is unwelcome.

In the winter, the bees need water to dilute honey. Brood only survives when the humidity is greater than 55%. Prof Seeley in his book The Life of Bees reported how the metabolic rate of bees was lowest at 10 °C and highest at -20 and +20 in a see-saw pattern. However, he did not ask the bees what temperature they preferred. Theoretically the manle of the cluster becomes damp due to the rate of respiration of bees, whereas the bees at the center are coasting with little need to expend energy. I anticipate that the inner bees would migrate outwards to get hydrated. But bees tend to be cleverer than our theories

Issues and Solutions

Bees are extremely able at managing humidity and temperature

We need to make it easier for them. Here is a rather technical and interesting discussion on Beescourc.com. At high humidity: i.e., the air outside is almost saturated. The slightest cooling causes precipitation. A study found that average humidity is 10 °C lower in plastic than wooden hives. (1) Help bees to maintain a steady temperature. Bees in warm hives stay active at lower temperatures and so are better able to change the internal milieux.

Wrap wooden hives

Wood is hygroscopic. The moisture in the walls of a wooden hive equilibrate with whatever surrounds them. Whereas with:

Insulate hive walls: so that the surface stays near ambient temperature.

Waterproof: wrapping to prevent water wicking in, which then evaporates and causes cooling.

Put absorbent mats above the crown board

Use in wooden hives to mop up water — Replace them when they are damp.

Provide shelter from the wind.

Use a wind break, a WBC or poly hive.

Provide adequate airflow

Air circulation removes heat and water. Bees, tell us what they prefer, or at least what they would do if they were living in a natural cavity. They block holes they don’t want. So they accept varroa mesh/screened floors, but propolise top vents.

Wooden hives: place matchsticks under the crown board;

Poly hives: In temperate climates, additional ventilation is unnecessary. If required, try using a slow ventilating “blanket” under the roof, as below.

Insulation at the top of the hive:

Rather than forcing the cluster to shelter under the crown board which acts as a heat sink, provide them with a dry, well insulated surface on which to cluster. 50 mm foam sheet style insulation under the roof dramatically reduces conductive and some convective heat losses and reduces winter losses (David Evans).

Take care when giving them liquid feed

Avoid feeding until the temperature is (>10 °C).

Avoid leaving dead-space inside the hive

Avoid supering too soon, in cold weather, or removing drawn combs too soon as they have thermal mass.

Give a timely varroa treatment in the autumn

Winter bees need to be healthy with a vigorous queen. Stress makes bees more susceptible to disease.

Condensation under the roof.

Poly hive Dynamics: my experience is that just as in poorly insulated homes, if humid air hits a cool wall it results in condensation. Some beekeepers claim that there is never condensation below the roof or inner cover in their poly hives. The picture of the roof of a poly hive (with three boxes in March) shows that I don’t agree! However, this arose when I’d used a wooden crown board with loosely fitting sheets of water-resistant insulation below the roof. Condensate that occurs like this can escape by dribbling harmlessly down the walls and out through the screened floor (OMF). But if you find your bees threatened by prolonged cool, foggy weather, or mould grows on the walls (I don’t know whether it ever does), you could try putting a quilt under the roof:

Quilt under the roof - venting air

The quilt consists of upholstery wadding (2.5 cm) with fly netting on its undersurface. To prevent the bees playing with the wadding, it is enclosed in a sleeve of garden cloth.

@ truewood.ca

@ truewood.ca

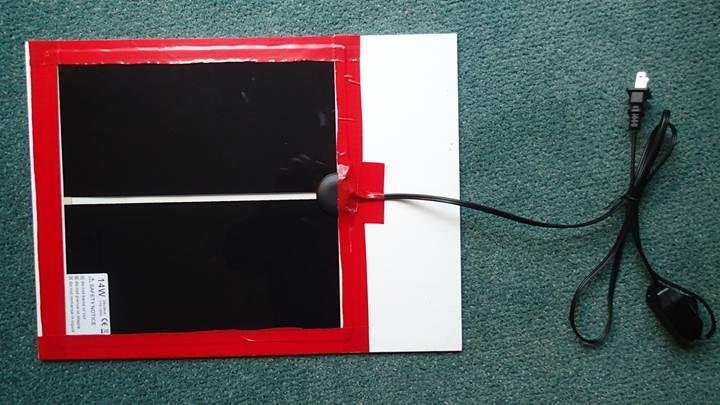

Heat pad

Bees benefit from bottom heat, for example, using a thermal pad (about 14 watt). This provides gentle heat. The mat is sold as a pad to warm pet amphibians. When used one month before the weather becomes favourable, it is excellent for stimulating spring build-up, so long as they have adequate store. In warmer climates, I anticipate it could cause premature colony build up.

Subsequently, winter losses are negligible, even in areas where temperatures barely reach 15 °C in May.

Their construction increases airflow, whilst not causing a draught. Whatever, they are effective and reduce relative humidity in the hives from 90%, to 80% (in West Canada).

H8

Finish this page or scroll down to learn a little physics.

The Science of Damp

This is a bonus that makes sense if you wish to read more about the subject. My objective is to explain how water interacts with pressure and temperature. The nomenclature is tedious as concepts are expressed in several ways, each one with its nuance. I’ve been rather repetitive, and I suppose that if you don’t fancy science you won’t read this, but surprise yourself and have a go.

Saturated air = 100% relative humidity = saturation moisture capacity (g/kg) so it condenses at dew point x °C = which occurs at a saturation vapour pressure (kPa = N/m2). These all refer to the point at which moisture in the air turns from one phase to another (e.g. gas to liquid). The consequence of these processes are evaporation, precipitation = condensation = fog = rain.

You will be familiar with putting salt in water. After stirring, the salt disappears — it dissolves in the water. If you add more salt, there comes a time when no more salt dissolves. But if you increase the water temperature, it will. Similarly, in the world of damp, the water represents the air and the salt represents the water in the air. In the figures below, the length of the arrows is proportional to the energy of the molecules.

The amount of water air can “hold” depends on the temperature and pressure. This makes sense if you think about weather forecasts. When air cools to a certain temperature, the air can no longer “hold” on to it; the water vapour turns into liquid. The “holding” is known as the moisture carrying capacity. The temperature at which vapour starts to turns to liquid is called the dew point. It is always lower than temperature. At that point, the air is saturated (it holds as much as it can) it has a relative humidity of 100%. The release of some water is known as condensation or precipitation. When air has not reached its dew point, it is called unsaturated.

The above description simplifies things. In reality, the dynamics relate to pressure, not “holding”. Humidity is determined by the pressure of water evaporating = vapour pressure. Vapour pressure is the pressure produced by the energy of gas molecules.

Saturation water vapour pressure is the pressure at which water vapour is in equilibrium with liquid water, rather like dew point. Its units are millibar, psi, mmHg, Atmospheres, or Pascals (Pa). A Pa is small, so it is usually considered as 1000 Pa = 1kPa. kPa is the metric unit and is equivalent to a pressure of one thousand Newtons per square meter. A Newton (N) is the force required to accelerate one kilogram by one metre per second.

Molecules in air don’t stay still. The warmer they are, the more they jiggle around. It is molecular movement which creates pressure. So, at last something meaningful. An explanation of a mass of molecules bashing in to things and so exerting pressure. At pressures higher than saturation vapour pressure, water will condense, while at lower pressures it will evaporate or sublimate.

This might help you: Imagine that you are holding a bath sponge almost saturated with hot water. If you squeeze it firmly, water will come out (it “condenses”). If you hold it in your hand, you should see steaming vapour rising (evaporation).

Condensation and evaporation are in equilibrium at this temperature and pressure.

Figure 2. At increased temperature, the energy of molecules increases so that the force of evaporation, vapour pressure increases. The amount of water vapour (w) it contains, compared with the maximal amount it could contain (m), is called humidity.

w/m × 100 = humidity %

Figure 3. Dew point is the temperature (°C) at saturation water pressure (kPa). It is the point when condensation begins.

Graph 1. The moisture holding capacity. This illustrates the maximum amount of water that the air can “hold’ at a given temperature in (g/Kg).

Humidity

Humidity is a measure of the saturation the air. When people discuss humidity, they are usually referring to relative humidity, which is an indication of how unsaturated the air is, compared to when it is fully saturated. It is the amount of moisture the air holds compared with the maximum it can hold.

Evaporation has a cooling effect: water molecules are loosely bonded together, breaking the bonds requires energy. Heat is energy. Years ago, butter coolers used this phenomenon, The butter was placed in a glass bowl over a terracotta pot containing water. As the water evaporated, it cooled the butter.

Condensation releases heat. This dynamic is not large enough to toast bread, but it may influence the weather.

High ambient humidity, could result in condensation on the edges of the bee cluster. The only way the cluster can prevent this is by increasing the temperature of the mantle or fan to evaporate the moisture. Humid air is lighter than less humid air at the same pressure and temperature (because nitrogen in the air is “heavier” than water: molecular weights N2 =14, H2O =10. If moist air went down rather than up, we wouldn't have any rain.

Humidity figures

Humidity and temperature levels usually change in tandem. Not so in a beehive. Nectar processing areas in the hive need to be at a low humidity (20%), and brood rearing areas (35%).

Meanwhile, the temperature in the brood nest / centre of the winter cluster varies between 18 and 35 °C. depending on whether they are raising brood. The temperature of the mantle is 7-9 °C.

Humidity greater than 79% renders varroa barely unable to breed.

Dew point

@Maths.com

Graph 2. A graph relates temperature, moisture capacity to the dew point. The top-line depicts 100% humidity, as in Graph 1. However, the graph also allows calculation of dew point at any temperature from 0 to 30 °C. The y-axis (labelled X) indicates moisture holding capacity g/Kg.

In this example, the hive with a temperature of 25 °C is at 40% humidity (black dot). As it cools, (which is represented by the green line) you can find the dew point.

For example, Southampton, on the South coast in the UK. Winter temperatures are between 9 and 3 °C, and the dew point is about 4 °C. The air around the cluster mantle is usually 9 °C. Any situation where the humidity is above the dew point will result in condensation. For example, if some air is 40% saturated at 10 °C the dew point is 5 °C. If it cools further due to cold weather or evaporation, the air carrying capacity falls, condensation occurs.

In a beehive that uses top ventilation to prevent condensation, the air warmed by the cluster is vented and cool air with a lower water holding capacity, and dew point, is drawn in. To prevent precipitation, the air around the cluster must be kept above dew point, and not less than 9 °C. So the cold air must be warmed and vented. Warming increases its water carrying capacity. This dynamic prevents condensation, but at the cost of putting the bees on a treadmill. Contrast this with bees in a poly hive. The warm air rises, less cooling occurs as less ventilation is required, but some condensation can arise, perhaps when there is too much space at the top of the hive.

Work this out: When the moisture content remains constant and the temperature increases, relative humidity decreases, but the dew point remains constant.

Graph 3

Graph 3. I heard a beekeeper say that freezing weather is good as it results in a tight cluster. However, the optimal temperature is 10 °C. (Prof Seeley - The Lives of Bees).

Detecting dying colonies

Etienne Minaud et al. found that the thermal amplitude within the nest is an indicator of colony health, effectively distinguishing between surviving and dying colonies, 4 weeks before the event occurred, with an accuracy of 96.8%. Moreover, he found that monitoring nest temperature enables the detection of the collapsing phases with an accuracy of 83.9%.

I’ve included the picture of temperatures in the cluster in case you find it first and think I’m talking tosh. The size of the cluster is compatible with prolific American bees, not with conservative English bees. An English winter cluster occupies approximately 1/3 of the width of a box. English bees never have to compete with an ambient temperature of minus 11 °C.

Causes of winter stress

Damp walls evaporate water — and cause cooling.

Excessive top ventilation causes upward airflow, loss of warm air, evaporation and cooling.

When the cluster’s surface area is large and it is chilled on all its surfaces.

Stress makes bees more susceptible to disease.

Supporting these notions is that bees in wooden hives perform well in warm weather.

Hive monitoring

There are numerous companies eager to sell you some kit. By buying bluetooth temperature/humidity monitors and a luggage weighing scale, you can do it on the cheap.

H8

(1) Alburaki, M., & Corona, M. (2021). Polyurethane honey bee hives provide better winter insulation than wooden hives. Journal of Apicultural Research, 61(2), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2021.1999578