Manipulations & Swarm Control

Abridged version

Avert the queen’s departure

Basic Assessment: Give an elementary account of one method of swarm control

Swarming is the bees’ mode of reproduction. From a beekeeper’s perspective, it is like a criminal fleeing the police. If the criminal’s car is far ahead, they may get away. The police prevent this by making a roadblock or rolling a strip of spikes across the road that puncture the car’s tyres. The roadblock and spikes are like the manipulations beekeepers perform to avert their bees from swarming.

Bees naturally want to reproduce, but it is the bete noire of beekeeping. Few bees mean little honey.

Colony size - honey volume - Swarming

A colony must be a specific size before it can make honey, which is also true of swarming; To swarm a colony requires a surplus of bees beyond those needed to care for a hive’s vital functions. Just as a human family can only go on a foreign holiday when it earns considerably more than its childcare costs. In the graph below, I’ve depicted this transition with a red line. The accumulative area under each curve and above the red line in the main flow (when there are plenty of flowers) roughly corresponds to how much honey a colony produces. There are five scenarios:

Colony population Time Series Graph

Orange, where both portions of a Split are united for the main flow

Green Split

Purple Swarm—If a large colony swarms in early April, there is hope of a small harvest.

Pale green is a portion of a split that has insufficient resources to recover or is ill.

Grey/black - no swarming or manipulation

The graph illustrates what happens when the colony population dive bombs due to a swarm, colony manipulation or poisoning. It takes an absolute minimum of 21 + 7 days for an egg to grow in to a forager. Before the main flow the colony re-invests its surplus into creating more bees, and by mid-June, it may have no stores and many hungry mouths to feed. If the main flow is late, they starve. If they swarm in June, a colony may still have so many bees that it will produce a surplus.

Colony dynamics and swarm control / swarm management

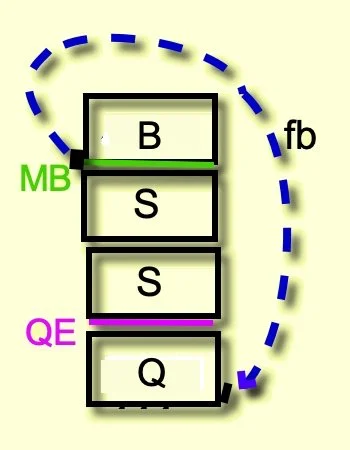

Please refer to Figure 1.

The text in the red boxes indicates modifiable factors necessary for the colony to swarm.

Sufficient brood

Sufficient foragers

Young bees

At least one queen cell

Presence of a queen.

Definitive swarm control methods rely on separating one of the three (underlined) factors from the other two.

Ground rules

1. Never kill a spare queen unless she heads an aggressive colony or is a drone layer. Put her in a small nuc (with bees, stores and emerging brood - the inner aspect of an arc of brood or where bees are emerging). She may be helpful later.

2. As far as possible, always leave the frames in the order you found them. Failing this, put brood centrally boarded by frames of pollen, comb, nectar, and stores. A box must contain a full complement of frames.

3. The parts of a split must be at least one meter apart, with entrances facing opposite directions.

6. If a portion lacks foragers, give it a frame of honey. After 24-48 hours, start feeding with syrup.

10. Manipulations require attention to detail. If a manipulation requires reducing QC to one, and you don’t, all your hard work will be undone.

11. Avoid using highly elongated queen cells or those on frames covered with drone brood, as they have a reputation for being duds.

12. I don’t want to insult your intelligence, but plan what equipment you’ll need before you start a manipulation. Quite often, in addition to a nuc or new hive, it is helpful to have one or two empty boxes (to sort frames) and a couple of spare hive stands (to make lifting easier).

13. If a colony has been queenless for a day or more the QC must be destroyed before re-introducing the queen.

Having a marked queen is helpful when performing manipulations

Marking the queen

A young Q will run around, making it almost impossible to find her. But keep your marking pen in hand. Here are examples of queen-catching devices. She may be pushed into a syringe, which is unlikely to hurt her.

The other cage is put over her and catches workers, too. It is good for catching the queen and transferring her to an introduction cage or marking device.

Marking involves dabbing a spot of paint on her thorax. I cover this in more detail elsewhere.

This cage is for catching the queen and transferring her into a travel/introduction cage.

Timing is critical when it comes to manipulations.

Thorne sells this little device. Turn the dial, and rather like an old-fashioned set-square for maths, you can read off what happens when.

Combine this with looking at a brood table.

Basic manipulations

Pagden artificial swarm (AS) — I mention this first because it is commonly recommended in introductory courses. In some parts of the UK, the first method that people learn is the Modified Snelgrove 2.

Swarm trap

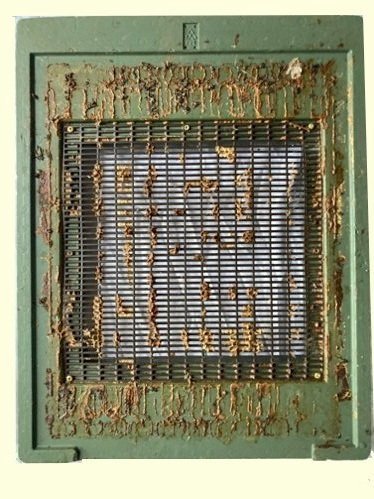

An easy method that necessitates a basic manipulation board. Paradise make a board for Langstroph, not Nationals. It is easy to make one, even if you only have basic woodworking skills.

Once you feel happy moving bees about, there are easier and better methods to try.

Artificial swarm (AS) The Pagden method

This is the most popular method, around my way for new beekeepers, which is sad because it is so difficult. It prevents swarming 100% IF DONE CORRECTLY. Once you are familiar with it try using an alternative method.

The Q stays home, with no QC in a box of comb along with the supers. She must have some drawn comb.

The brood is moved away. Consequently, the foragers fly home. The portion moved away must make just one Q, so destroy all but one QC.

Received wisdom is that you leave a open queen cell containing a fat larva rather than a closed QC.

The part that is moved away has to make a new Q but has plenty of young bees.

You may hear of a modified artificial swarm called a Heddon. It is unnecessary but works like this: One week after the first manipulation, the “mobile home” portion is moved 180 degrees to the other side of the home position (where the “swarm” resides). This means more flyers boost the swarmed portion.

The queen-less part is left alone for 28 days before you peep in and look for eggs. The Q occasionally takes several weeks to get laying (max. five weeks); if you are worried after one week, a test frame may be unreliable (I’m not sure), so you will have to stay worried for a week longer.

How an artificial swarm works

Fliers rejoin the Q at the home position.

The consequence of an artificial swarm is that the “swarming” colony (at the home position) tends to dwindle as it has inadequate young bees. Although initially, the foragers can bring in a fair bit of nectar.

The queenless portion kicks its heels for several weeks until it gets a new Q.

A vertical “Pagden”: Perform this split for control or swarm prevention. The brood and bees are put up top with a manipulation board entrance facing away or to the side of the usual entrance. Initially, obscure the central area of mesh on the manipulation board. Preferably, some supers separate the brood boxes, as in a Demaree. When the new queen is laying, reveal the QE and re-adjust the entrance orientation for a fortnight so that it faces forward. Subsequently, the box containing the new queen is put above the old queen, separated by a QE (or no QE if you prefer).

The queens tolerate each other for the rest of the season and are unlikely to swarm as the mandibular pheromone levels remain high. Alternatively, if you want to do a lot of work, the top box could be removed to another hive stand according to the moving hive rules.

Swarm/Queen Trap

The Q is trapped beneath the excluder, stopping her from swarming. As the virgin queens emerge, they fight until only one or the old queen survives.

Leave the colony alone for 28 days. After this, reverse the entrances so that the Q can go out to mate.

If there is too much brood to fit in one box, put extra frames above the Swarm Trap. Kill all the QC on these frames, and repeat after six days.

This can be used as a regular method of swarm control and must be particularly useful for commercial beekeepers who do not have time to do splits. It is also helpful in poor weather when a proper manipulation is impossible. I suppose there is a danger that the virgin Q will fail to mate in time. The new Q sometimes lays alongside the old Q as in a perfect supersedure.

The trap does not resemble anything bees do when they swarm; it feels unnatural. Don’t do it with your favourite queen. So yes, it works, but unpleasant things happen. One of my colonies suffered the Inkpin Joe effect. Another time, I found a Q trying to crawl with half her legs missing.

A big plus is that the bees in robust colonies may continue foraging, although more often, I suspect that the bees are in a “suspended swarming mode” and go in and out without achieving anything. It is like a human desperate to pee. Whilst hanging on, they don’t get any work done.

The undersurface becomes covered with propolis

Paradise Honey extols this device as a revolutionary innovation. It isn’t. A Bailey board is much the same, but the Swarm Trap has an entrance reducer, not just an entrance.

With the previous Paradise trap design, the concept was that if the brood was in one box, the trap was left in the hive as a regular QE. But the device kept falling apart. The new design could be used in the same way, but it engenders gazillions of propolis on its undersurface.

To control swarming, when any QC arises no thought is required, shut the hive entrance and open the upper entrance. Job done.

Uncontrolled Swarming

The Q has emerged from her cell. On rare occasions, the bees will seal an empty QC

It happens to the best beekeepers. A prolonged period of poor weather prohibits inspections, and when the weather breaks, several queens have emerged.

The old Q departs with the prime swarm. There is a danger that a succession of virgins leave as secondary swarms called after-swarms, post-prime or casts. Indeed, a colony can throw off casts numerous times. It happens like this:

Eight days after the old Q has departed, some virgins emerge and fight. But workers stop some Q from emerging and keep them safe. They sit on the top of the QC and feed the Q through a slit in the cap. But the workers allow a new Q to kill the other queens in their cells.

If the beekeeper does not intervene, one of the protected queens fly away with half of the remaining bees. Subsequently, every day or every few days castes leave until barely any of the colony remains.

To stop the process, release all the queens from ripe cells and destroy the rest of the QC, or release one and destroy the rest. If you intervene before any queens emerge, you can get some QC (to replace your queens).

If none of the queen cells are ripe open a number to judge their age and come back later to do the business.